Notes from Appalachia

On the trail of Trump voters in eastern Kentucky

One of the core principles of the Rural-Spatial-Justice project is that place matters. Coverage of elections may be dominated by national campaigns and issues, by the big personalities, and by divisions in voting behaviour between social groups, but people make their decision about how to vote in particular places, informed by their lived experience in that place as well as their assessment of the relative prospects of parties or candidates locally.

We’re especially interested, of course, in voting behaviours in rural places, many of which have moved in recent elections towards support for disruptive parties and candidates that challenge the conventional political mainstream. In the USA, Donald Trump has consolidated his hold on non-metropolitan counties, widening the rural-urban gap in voting patterns (although in absolute terms more Trump supporters live in major metros than in rural counties). This trajectory has been noted in newspaper headlines about the divide between rural America and urban America, and has spawned studies that have linked support for Trump with rural experiences of place-based despair and frustration.

However, the more that we focus in on places, the more that we see that rural areas are not politically homogenous. Trump’s rural heartland is made up of several different socio-geographical components with different characters: the disaffected farming vote in the Great Plains and Mid West; libertarian-leaning voters in the West, fearful about the Californification of their states; the religious, conservative Deep South; hollowed-out small towns everywhere.

And then there’s Appalachia.

Appalachia was not historically a Republican stronghold. Quite the opposite. Yet, the sharp swing to Donald Trump recorded in Appalachia the 2016 election sent journalists scurrying to the region to discover the secrets of its political conversion. The iconic significance of what sociologist Dwight Billings has dubbed ‘Trumpalachia’ (1) to President Trump’s voter base was further reinforced by the sensational success of J. D. Vance’s memoir, Hillbilly Elegy. Published five months before the 2016 election, Vance’s self-described ‘memoir of a culture’ was seized upon by commentators on the right and left alike as a window into the minds of white working class Appalachian Trump voters. My paperback copy carries a quote on its cover from the UK’s Independent newspaper declaring it to be, with a bit of a stretch, “a great insight into Trump and Brexit”. More recently, the publication last year of Arlie Russell Hochschild’s latest book, Stolen Pride, based on fieldwork in Pike County, Kentucky, between 2017 and 2020 and the follow-up to her bestselling Strangers In Their Own Land that had also been treated as an ‘explanation’ for Trump’s victory, is likely to reignite the dissection of Appalachia as Trump territory in his second presidency.

In selecting eastern Kentucky as one of the case studies for Rural-Spatial-Justice we are very aware that we are also outsiders dipping into Appalachia and are also prone to risks of academic tourism, stereotyping, and coming away with a superficial reading of the region that confirms a pre-existing thesis. To try to guard against these traps, we have been preparing for the research by seeking to get a deeper background picture of the region. At the end of March we made a short scoping visit to Kentucky. In additional to scouting out prospective case study locations we spent time talking to scholars and students in the Appalachian Center and other faculties at the University of Kentucky to get their insights and advice. We came away, too, with a long reading list that we have been steadily working through.

In this essay, I pull together some of our thoughts from this engagement, the questions that they prompt for investigation, and how these might shape our approach to the case study research.

A Trump Heartland?

Support for President Trump in eastern Kentucky is genuine and proud. As we drove around the towns and valleys of the region, we repeatedly encountered Trump-Vance signs and banners, in yards and windows, or hanging from fences and porches. Sometimes they were accompanied by the Stars and Stripes; once or twice by confederate flags. On one occasion we saw a life-size cut-out of Rambo, with Trump’s face in place of Sly Stallone.

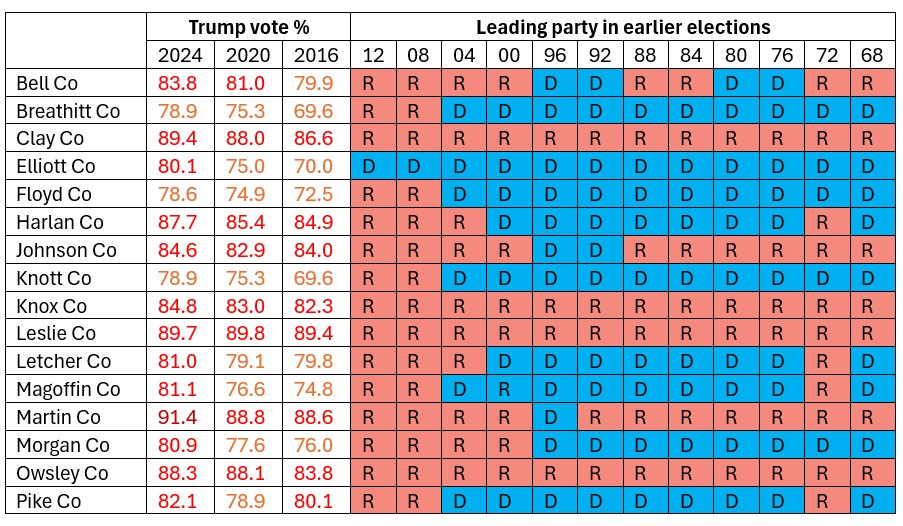

The counties that we had picked to visit as possible sites for fieldwork had all cast 80% or more of votes for Donald Trump last November. However, their political trajectories were surprisingly varied. Magoffin County, a two-hour drive east of Lexington, for example, has been in the Republican column since 2008, giving Trump 81% of the vote in 2016. Yet, John Kerry had won there in 2004, and it had only voted Republican twice between 1964 and 2000. Neighbouring Johnson County, in contrast, has consistently voted Republican since 1916, with the exception of narrowly backing Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996. To the north, meanwhile, Elliott County only flipped to the Republicans in 2016. In 2012 it had been the last majority white county in the South never to have voted G.O.P. in a presidential election. Donald Trump is the only Republican presidential candidate to have won there.

This hotch-potch of political history cautions us against sweeping statements and totalising theories about the turn to Trump in Appalachia, as well as raising questions about the role of place in shaping voting behaviours within eastern Kentucky and about how Donald Trump has been able to achieve a clean sweep in the region.

A Left-Behind Region?

The most common generalisation about Appalachia is that it has been ‘left-behind’ economically and culturally by globalisation and neoliberalism. The application of the epithet to the region is not new. Historian Ronald Eller describes how Appalachia was represented in the 1960s as “an underdeveloped region rather than a depressed area” (2) by local politicians keen to distinguish it from the economic ills of major cities and to emphasise the structural obstacles to growth that needed to be overcome. Over the next three decades, government programmes succeeded in substantially cutting the poverty rate across Appalachia as a whole, but in the mountainous rural counties of eastern Kentucky, poverty remained stubbornly persistent.

In a swathe of counties from McCreary County in the south-west to Martin County in the north-east, at least 25% of the population were living below the poverty line in the latest estimates, peaking at 38% in Wolfe County, placing them among the poorest counties in the USA. In three counties (Bell, Magoffin and Wolfe), mean annual household income was below $50,000 per year. On both measures, however, material deprivation has been significantly reduced in the region since the start of the century.

Rural poverty tends not to be as concentrated or as visible as urban poverty. The towns we visited were well maintained, with little obvious graffiti or vandalism, or signs of rough sleeping. But as our eyes adjusted, the indicators of poverty became more apparent: the ubiquity of trailer homes, the pawnbrokers and thrift stores, the proliferation of Dollar Generals with more shelves of hunting gear than of fresh food.

The Rise and Fall of King Coal

In their landmark study of Clay County, The Road to Poverty, Dwight Billings and Kathleen Blee traced the roots of the region’s poverty to the pervasiveness of subsistence farming in the nineteenth century. As little agricultural produce left for external markets, few earnings flowed back in, restricting the endogenous capital available in the region for investment in development. Consequently, as eastern Kentucky’s timber and especially coal resources became sought-after, they were exploited by outside investors who took advantage of the large, cheap, pool of surplus labour in what was later characterised as a model of internal colonialism. Even in the 1980s, a survey found that the majority of land in Appalachia was owned by absentee landowners, the greatest share by large corporations. (3)

Farming has largely disappeared in most of south-eastern Kentucky, except in fringes such as Elliott County and Morgan County, where fields emerge from the forests and mountains. Even here, the decline of tobacco cultivation has removed a valuable cash crop (although it was never as dominant as in counties further west). Mining, too, proved to be an unreliable employer, cycling through peaks and troughs. The initial rush was followed by deep recession in the 1930s; a wartime boom gave way to bust in the late 1940s and 1950s, with more than a third of the population of eastern Kentucky migrating away; and while coal’s fortunes continued to fluctuate in the 1960s and 1970s, it was on a clear downward path.

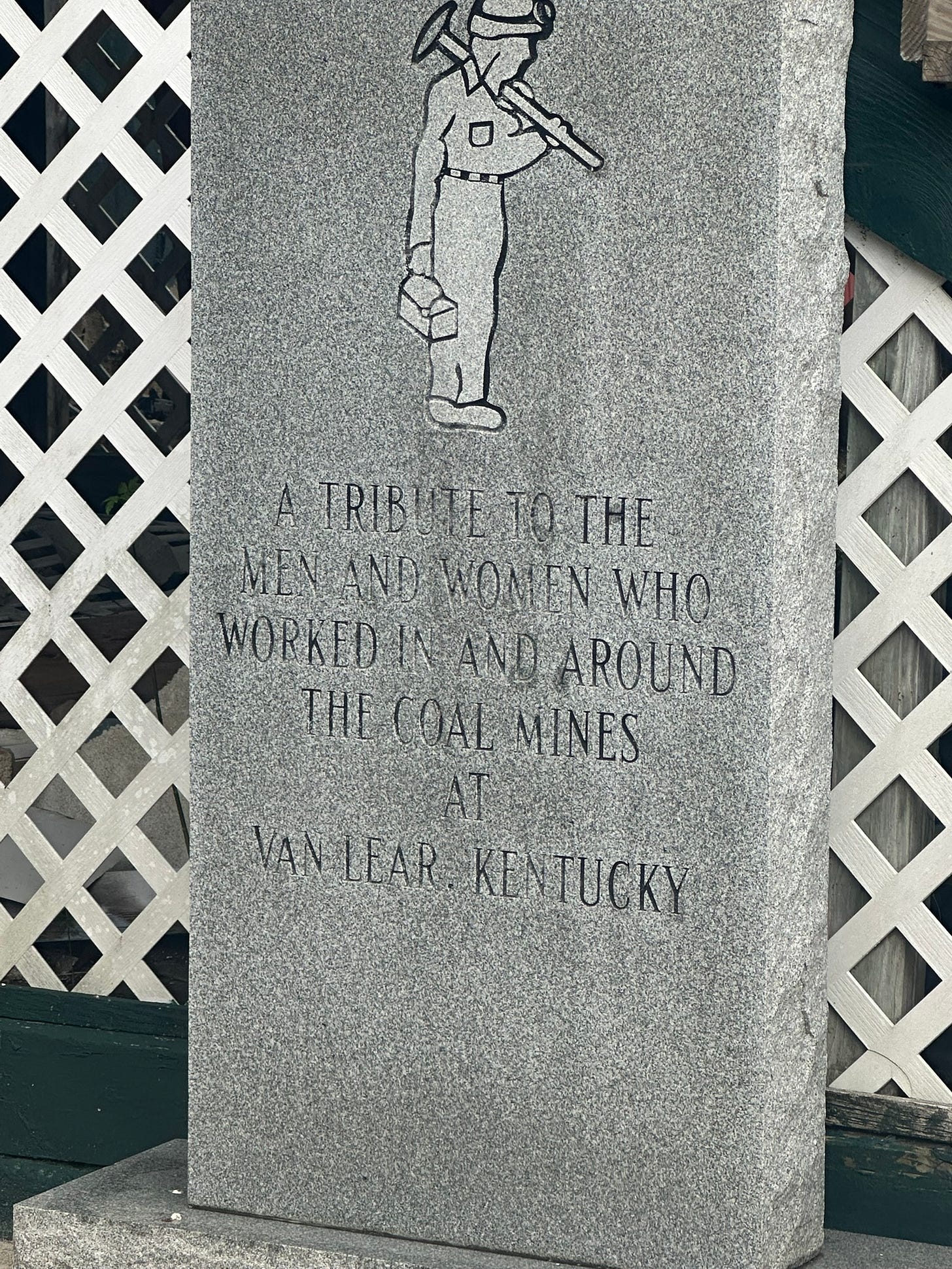

The innovation of strip mining, using new technologies to extract coal from the surface rather than through underground pits, promised rejuvenation for the coal industry in the 1970s. Yet, strip mining was opposed both by local communities – who objected to the environmental scaring of mountain top removal – and by the owners of underground mines, who feared, correctly, that the lower cost mining method would undercut their product. Accordingly, the economic benefits of the strip mining boom were unevenly distributed, socially and geographically. Arlie Russell Hochschild depicts Pikeville as a prosperous mining town in the 1980s, where there were “Mercedeses in [the] school parking lot” and more than a hundred millionaires living within a ten-mile radius (4). However, in places like Van Lear, in nearby Johnson County, the setting of local girl Loretta Lynn’s Coal Miner’s Daughter, the collieries had already gone.

Topographically, eastern Kentucky is reminiscent of the South Wales coalfield, with settlements spilling along narrow valleys between the rocky fingers of forested hills. Yet, whereas in South Wales the pits also occupied the valleys and their traces and legacy are still strongly present long after coal-mining has ceased, in eastern Kentucky we saw little visible evidence of mining, even though we knew that mining operations were active in the counties we visited. Today’s mines are raised out of sight on the mountain tops, only coming into view from the windows of our Delta plane as we left Lexington for Atlanta.

In 2022, coal mining employed 4,273 workers in Kentucky, or around 2% of the total workforce of Appalachian Kentucky. Only two counties – Harlan and Leslie – are still categorised as ‘High Mining Concentration Counties’ by the USDA Economic Research Service. Writer Elizabeth Catte notes that those still working as coal miners are not badly paid, earning on average around $60,000 to $90,000 a year. “The real forgotten working-class citizens of Appalachia,” Catte observes, “are home health workers and Dollar General employees” (5). In other words, poverty in eastern Kentucky is longer due to employment in mining, but rather the failure to replace coal mining with alternative good manufacturing or service-sector jobs.

Mining Politics and Invisible Power

The demise of coal mining has changed the political dynamics of eastern Kentucky. Like many mining regions, Appalachia was historically associated with union militancy and industrial conflict. The long-running Harlan County War of violent confrontations between mineworkers and mine operators in the 1930s inspired the haunting folk melody, Which Side are you On?, penned by miner’s wife Florence Reece on the back of a calendar after her home had been terrorised by company enforcers. As recently as 2019, Harlan County miners blockaded a railroad track in a dispute with the coal company.

Such antagonistic industrial politics made sense when coal was king and the major struggle for workers was with the coal companies for a fair share of mining profits. However, as mining has contracted and as the key threats are now perceived to come from outside – from foreign imports and from environmentalists wanting to end dependency on fossil fuels – so miners and their unions have increasingly found themselves on the same side as mining companies.

The foundations of the unexpected alliance were perhaps always present, buried like the coal seams deep beneath the surface tension. In 1982, political scientist John Gaventa published his doctoral study of power relations in a mining valley that crossed the Kentucky-Tennessee border near Cumberland Gap. In Power and Powerlessness, Gaventa followed the radical three-face theory of power developed by his Oxford supervisor, Steven Lukes, to argue that beyond the ‘visible power’ of public politics and the ‘hidden power’ of structural biases, there was also in the valley ‘invisible power’ involving “the internalization of powerlessness so that people who experience it, the victims of an unjust status quo, come to believe in its legitimacy” (6).

Gaventa’s main case study for invisible power focused on the internal politics of the mineworkers’ union in the 1960s and the question of why miners in the valley had not backed a reformist candidate against a corrupt and dictatorial union leadership. However, as he notes in a later essay, it can also be applied to the power of the coal companies and perhaps by extension to the unchallenged dominance of mining in political discourse in Appalachia and the unquestioned assumption that the interests of the mining industry and the interests of the region are the same, even when most mines have closed (and even despite the social and environmental impacts of mining).

One of the explanations put forward for Appalachia’s turn to Trump in 2016 is that voters in the region rallied to his pro-fossil fuel agenda after Hillary Clinton’s unguarded comment that her policies would put “a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of Work” (7). But, why should Clinton’s slip have had such a decisive effect with the vast majority of voters in eastern Kentucky who no longer owe their livelihoods to coal, even indirectly? Understanding the invisible power of coal mining as being so fundamentally engrained in the identity of the region that voters instinctively push back against any apparent attack on the industry could help to resolve this paradox.

[As an aside, re-reading Power and Powerlessness, I was struck by the parallels between the ‘myths’ that Gaventa identified being used in the exercise of invisible power against reformists in the union, and some of the tropes circulating in current American politics. The reformist union candidate was accused of being in the pay of the corporations; it was falsely suggested that he would take away workers’ pensions; unspecified ‘outsiders’ and ‘radicals’ were portrayed to be seeking to destroy the union; and ‘expertise’ was ridiculed. Indeed, Gaventa observed, “if ‘corporations’ and ‘rich people’ are terms of abuse in Appalachia, so too are middle class, social reformers (‘instant experts’) and company informers” (8).]

Bipartisanship or Voter Realignment?

In countries with class-based party systems, miner militancy made coalfields strongholds of left-wing socialist and social democratic parties. In the United States, however, the pattern of party allegiances is more complicated. J. D. Vance’s Papaw may have been a Democrat “because the party protected working people” (9), and the mining community in Gaventa’s study may have voted Democratic “since the days of the New Deal and the union” (10), but the coal industry’s influence in local politics in eastern Kentucky was bipartisan. Ronald Eller, for instance, observes that in 1950s Harlan County, “the secretary of the coal operators’ association was the chair of the county Republican committee, while the president of the association was the head of the county Democratic committee” (11). In Clay County in the 1960s, Dwight Billings and Kathleen Blee record that Republicans dominated county government, but worked closely with the local Democrats whose party controlled the state government, a division of labour that they describe as “typical of many eastern Kentucky counties” (12).

At the county level, local Democratic and Republican parties were commonly the creatures of certain individuals or families, often closely tied to coal companies or their agents, breeding a culture of clientelism and corruption. In this environment, personality-driven factionalism was arguably more important than ideology or national partisanship in shaping voting behaviours, possibly explaining the variegated electoral geography of eastern Kentucky. The consolidation of this electoral geography behind Trump in 2016, therefore, could be read as the final erasure of old-style Kentucky politics. Or, alternatively, it might be a sign that personality-driven voting is alive and well, with voters backing Trump the individual rather than the Republican party (or even the MAGA movement).

Afterall, several eastern Kentucky counties that overwhelmingly voted for Trump in 2016, 2020 and 2024, were won by the Democratic Governor of Kentucky, Andy Beshear, in the 2019 gubernatorial election – including Breathitt, Elliott, Floyd, Magoffin and Wolfe counties. Moreover, 79% of voters in Breathitt County are registered Democrats (as are 76% in Wolfe County and 71% in Elliott County). Leafing through the local newspaper in Powell County, I read that the newly elected Republican county chair had launched a registration drive. “We only need 398 registered Republicans to surpass Democrats in Powell County,” he said, “I believe most people in our community align with Republican values, and it’s time for our voter registration to reflect that”. In November 2024, Donald Trump had received 4092 votes in Powell County, compared to 1174 for Kamala Harris.

These statistics suggest that political allegiances in eastern Kentucky are more fluid than the landslide vote for Trump implies. Are Trump voters in Appalachia not yet sold on the Republican party? Could they revert to a future Democratic candidate when Trump is no longer on the ballot? Or, is it evidence of an unfinished revolution, with the formalities of voter registration lagging behind a de facto realignment?

Legacies of the War on Poverty

When Elliott County defied the regional trend by voting for Obama in 2012, the Huffington Post sent a journalist to investigate. They reported that the county’s fealty to the Democrats was owed to its relative poverty and locals’ gratitude to the Democrats for government programmes stretching back to Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. “Elliott residents feel a deep personal connection to the Democratic Party, through the opportunities are assistance the government has provided”, the article stated (although it can also be read as more evidence of the power of personality politics – in this case, the influence of the long-serving Democratic State Representative). Yet, for the Huffington Post, Elliott County was a remnant of an electoral geography that was on the turn:

“When the county supports a Republican presidential nominee – and recent election results suggest that time might be soon – it will mark the final victory of conservative social values over progressive economic interests in the region, and the end of a once-powerful Democratic voting bloc whose roots can be traced back to the Civil War.” (The Huffington Post, 10 May 2013).

In the progressive economic tradition of government intervention, the New Deal was followed by the War on Poverty, launched by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. Although a national campaign, the War on Poverty was largely motivated by the extreme poverty found in Appalachian coal camps. It sent poverty workers and volunteers into Appalachian towns and valleys, established Jobs Corps and community action agencies, and funded local projects, with an ambition to modernise mountain culture. As Ronald Eller writes, for Appalachia, “the War on Poverty was as much an attitude, a moral crusade, as a set of programs” (13). The War on Poverty did not however tackle the structural foundations of the region’s inequalities. Rather, it formed another dimension of the invisible power of coal. Noting that coal companies routinely denied local residents permission to use company roads when public roads were washed away by flooding, Elizabeth Catte states: “What the War on Poverty did was come to communities to rebuild roads. What the War on Poverty didn’t do was help poor people deal with the fact that they lived in a world where those who hoarded wealth would rather see them starve than share” (14).

Operating in parallel to the War on Poverty was the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), founded in 1965. The ARC was one of the first attempts at comprehensive regional planning in the United States and imported the latest ideas from Europe of stimulating regional economic development through investment in metropolitan growth poles. As Ronald Eller observes, this concept translated poorly to rural Appalachia, where the larger urban centres are located on the periphery. Following lobbying by local politicians, the approach was adapted to focus on county seats and small cities. Places such as Paintsville, Prestonburg, Pikeville and Middlesboro benefited from development and modernisation, with economic diversification and new job creation, while few funds flowed into more remote rural communities. Manufacturing industries that were attracted to replace mining jobs stuck close to the new highways that connected these towns, creating few opportunities in smaller communities. Indeed, the highways had been consciously designed to facilitate commuting to employment in cities – and became conduits for migration out of the region.

As such, the ARC intensified rural-urban inequalities within Appalachian Kentucky. More than that, it appeared set to dismantle Appalachian rural culture, Ronald Eller drawing on a contemporary Harpers magazine article to surmise that:

“This meant that those working to improve the quality of life in Appalachia must give up ‘the old American dream … that [we] might return somehow to the pastoral life in country villages and small farms.’ It also meant that little, dying towns in the mountains must ‘be encouraged to die faster’ and that millions of rural mountaineers would ‘have to move away from their creek bottom corn patches and played-out mineheads’” (15)

The ARC still functions, with a much denuded budget, funding placed-based projects such as a downtown refurbishment scheme we saw in Pineville, Bell County. More broadly, we found little evidence and little expectation of government assistance. On our way into Appalachia, we stopped at the Kentucky Steam Heritage Corporation’s museum, set in the vast former marshalling yard of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad at Irvine, Estill County. The tracks had carried millions of tonnes of coal out of the mountains before they ceased operating in 2016. The ex-railway-worker volunteer who greeted us talked passionately about the museum project and the challenge of raising funds. We later reflected that had the conversation been about a similar project in Europe, talk would soon have turned to EU or government funding, or at least grumbling about the lack of government support. In Kentucky it seemed not to even register as a possibility.

The omission of course reflects the difference between American and European attitudes towards the state and the role of government in rural development. Nonethless, it is noteworthy in the context of a region that has arguably received more government funding for economic development over time than any other in the United States. That made us wonder about how investments such as the ARC, the War on Poverty, and, going back further, the New Deal are viewed by local residents. Are they remembered fondly? Did gratitude to the Democrats for them really shaping voting habits into this century? Is there bitterness that they have gone? Anger at neoliberal elites who rolled back state intervention? Resentment towards other social groups elsewhere who are today’s recipients of government assistance? Or, are the programmes considered to have failed? If so, has the experience hardened opinion against welfare and government intervention in the economy?

Whose Failure?

Dependency on government assistance arguably always sat uneasily with values of independence and self-reliance that are entrenched in Appalachian culture. The historian Harry M. Caudill, who reported on the poverty of eastern Kentucky and did much to shape external perceptions of the region, wrote back in 1963 that “nothing in the history of the mountain people had conditioned them to receive such grants with gratitude, or to use them with restraint”. Welfare payments, he suggested, became “a lode from which dollars could be mined more easily than from any coal seam” (16).

Six decades later, one of the main arguments of Arlie Russell Hochschild’s book is that the right-ward shift of Appalachian voters is associated with injured pride and a sense of shame at their economic predicament. She tells the story of individuals who blame themselves for business failures or being trapped in poverty, for not succeeding in attaining the ‘American dream’. Contrary to the exploitation of welfare portrayed by Caudill, Hochschild’s subjects subscribe to a ’bootstrap individualism’, believing that people “get rich because they work harder” (17).

The tension between dependency and individualism is central as well in J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, and in his own life story. Vance credits the values of individual responsibility, hard work and self-motivation instilled in him by his Appalachian grandmother (Mamaw) for his climb into the affluent upper middle class, yet he also blames Appalachian culture for the indolence and ‘bad decisions’ of his relatives and neighbours who failed to follow the same route of social mobility. Vance positions himself as straddling two white working class worlds: one “old-fashioned, quietly faithful, self-reliant, hardworking”, the other “consumerist, isolated, angry, distrustful” (18). He observes both worlds in his Mamaw’s Kentucky home town of Jackson in Breathitt County:

“Jackson is undoubtedly full of the nicest people in the world; it is also full of drug addicts and at least one man who can find the time to make eight children but can’t find the time to support them. It is unquestionably beautiful, but its beauty is obscured by the environmental waste and loose trash that scatters the countryside. Its people are hardworking, except of course for the many food stamp recipients who show little interest in honest work. Jackson … is full of contradictions.” (19)

Vance’s political journey to the right began while working in a grocery store in the peri-Appalachian city of Middletown, Ohio, where his family had moved. There, he claims, he witnessed people gaming the welfare system, purchasing packs of soda with food stamps to sell on for cash, running up large tabs, paying with food stamps while chatting on cell phones. The young Vance “could never understand why our lives felt like a struggle while those living off of government largesse enjoyed trinkets that I only dreamed about”. In conspiratorial conversations with his Mamaw, they “began to view much of our fellow working class with mistrust” (20).

It is easy to see why Hillbilly Elegy appealed to conservative neoliberals whose ideological conviction that welfare is disempowering it appeared to vindicate. It’s possible too to read Hillbilly Elegy as an insight into conservative-minded working class voters who, as Vance notes, started to turn to Nixon in the 1970s and Reagan in the 1980s in objection to their hard-earned tax dollars going on welfare payments. It is more difficult to find in Hillbilly Elegy an explanation for the movement to Trump in 2016 of the large majority of voters in eastern Kentucky, which must include many living in poverty, in receipt of welfare, and belonging to the section of the white working class that Vance stigmatises and rejects.

Vance himself offered a more direct explanation in an interview with a Washington Post journalist, observing that “the simple answer is that these people – my people – are really struggling, and there hasn’t been a single political candidate who speaks to those struggles in a long time. Donald Trump at least tries” (21). Leaving aside the veracity of this statement – Dwight Billings for one argues that it overlooks Bernie Sanders among others – it is notable in shifting perspective, away from the failings of the Appalachian working class to the failings of the Washington political class.

When J. D. Vance was selected as Donald Trump’s running mate in 2024, he moved from being a commentator to a being a major political player and his narrative was incorporated into G.O.P. campaign rhetoric. In his speech to the Republican National Convention, Vance reprised the story of his Appalachian and rust belt roots, but with blame for the region’s woes now firmly attributed to liberal elites, and particularly Joe Biden:

“I grew up in Middletown, Ohio, a small town where people spoke their minds, built with their hands, and loved their God, their family, their community and their country with their whole hearts.

But it was also a place that had been cast aside and forgotten by America’s ruling class in Washington.

When I was in the fourth grade, a career politician by the name of Joe Biden supported NAFTA, a bad trade deal that sent countless good jobs to Mexico.

When I was a sophomore in high school, that same career politician named Joe Biden gave China a sweetheart trade deal that destroyed even more good American middle-class manufacturing jobs.

When I was a senior in high school, that same Joe Biden supported the disastrous invasion of Iraq.

And at each step of the way, in small towns like mine in Ohio, or next door in Pennsylvania or Michigan, in other states across our country, jobs were sent oversea sand our children were sent to war.”

Speech to the Republican National Convention by J. D. Vance, 17 July 2024.

Later, in a campaign stop in rural Kent County in Michigan, Vance reportedly told voters that they’d been “betrayed” by “America’s ruling class in Washington, D.C.”.

Through these various pronouncements, from Hillbilly Elegy to the Michigan campaign stop, J. D. Vance has refocused the language of blame. From castigating fellow white working class Appalachians for their failure to escape the poverty trap, he moved to attacking political elites for failing rural and small town communities. In other words, he shifted from a neoliberal framing of Appalachia’s problems to a populist framing.

Although Hillbilly Elegy received plaudits from both left and right, nationally and internationally, it has been roundly critiqued by Appalachia-based scholars and writers. In collections such as Appalachian Reckoning, contributors accused Vance of misrepresenting and patronising the region’s residents, criticised the lack of empirical and theoretical rigour, and questioned the book’s ethnic politics (though the volume does include one chapter ‘In Defense of J. D. Vance’). However, I have yet to find an academic study or survey that has examined what the general population of eastern Kentucky think of J. D. Vance or his portrayal of their culture, or whether they subscribe to his diagnosis of blame for deprivation in their communities (the nearest is an article in the Daily Yonder, which interviewed residents in Breathitt County, finding mixed opinions). These are questions that we will need to return to in our research.

Of Churches and Prisons

Switching perspective from the condition of Appalachian communities (and external representations of them) to the claimed failings of the American political elite towards the region requires attention to be paid to how residents in eastern Kentucky view the outside world and how such perceptions are formed and shaped. The obvious answer to the latter question is through the plethora of partisan right-wing TV channels and radio talk shows and through the echo chambers of social media (Hochschild notes of one couple in Pike County she features, “news of politics came to them through their cellphones: Twitter, TikTok, Facebook” (22)).

Yet, such is the omnipresence of right-wing messaging through media and social media across the USA that it cannot explain variations in electoral geography. We need to understand how people make sense of political news and opinion in relation to their place-based lived experience and how political beliefs and behaviours are shaped by social interactions within place. Electoral geographers have traditionally referred to this as the neighbourhood effect and have used it to explain why workers in predominantly middle class areas are more likely to vote for conservative parties than their peers nationally, or conversely the tendency of middle class residents in working class districts to vote to the left.

It matters where such opinion-shaping conversations take place and who is involved. Most of the counties in eastern Kentucky are dry (meaning that no alcohol can be sold), or at least moist (meaning that alcohol is only sold in the county seat). A consequence of this prohibition is that there are few bars, pubs, or clubs, which elsewhere are places where members of a community gather, gossip, grumble, discuss politics and influence each other as they put the world to rights. In dryish Kentucky there are several alternative sites that could perform this function, from the local Applebees to locker rooms at sports facilities, but the ones that stood out to us were churches. Like much else, religion in Appalachia has undergone restructuring, with small, free-spirited mountain chapels supplanted by larger churches in otherwise depleted downtowns or alongside highways, often affiliated with one of the big evangelical denominations – Assembly of God, Baptist, Church of God, Gospel, Pentecostal.

A lot has been written about the influence of evangelical Christianity in American politics, and its followers’ support for Donald Trump. However, we are less interested in the role of personal faith or of charismatic preachers than in the social function of churches in their community. Although J. D. Vance has observed that regular church attendance in Appalachia is lower than is commonly assumed, it is reasonable to postulate that for many residents the church is nonetheless a major part of community life, with church-based activities involving more than just Sunday morning services. Might such activities be spaces in which residents talk about what is happening in the community, in the nation, in politics? If this is the case, what difference does it make that these conversations are happening in the shadow of socially conservative teaching?

Churches are not the only feature of the regional landscape that could have a role in a neighbourhood effect. Outside West Liberty in Morgan County we passed by the walls of the Eastern Kentucky Correctional Complex, one of the prisons that have proliferated in Appalachian in the wake of coal. The economic benefits of building prisons in rural counties are debated, but we again are more interested in the social impact. Elizabeth Catte suggests that most inmates “would be African American, arriving from the Northeast or lowland South” (23). If so, could the most direct contact that many local residents have with people from major metropolitan regions, or indeed with non-whites, be as prison staff and prisoners respectively? How might that colour the perceptions of east Kentucky residents of metropolitan America? Of African Americans? Of federal government policies and the interests of metro-based liberal politicians?

Back to the Future

It is small step from drawing distinctions between rural and urban regions to imagining these as conflicting cultures to forming grievances about unfair treatment that can form the basis for political mobilisation. In Stolen Pride, Arlie Russell Hochschild recounts a conversation with Alex, a Trump supporter from Pike County, in which he describes his experience looking for work in Lexington and getting repeatedly knocked-back when he said where he came from – “even within Kentucky the city looks down on the country”, he told Hochschild. Then he continued, “’when I hear Facebook, Instagram, Twitter posts with city liberals criticizing rural people, I absolutely’ – he drew his head back as if restraining himself – ‘do not need that.’” (24).

Populism maps such festering resentments, such feelings of unfairness, on to its core organising framework of ‘us versus them’, ‘the people versus the elite’, spatialising the latter as ‘rural people versus urban elites’. In this way, populism politicises spatial identity, but it also politicises time through deployment of nostalgia as one of its most potent weapons – arguably perfected in Trump’s slogan, ‘Make American Great Again’.

It may appear odd for nostalgia to appeal in a region where the past was characterised by extreme poverty. Yet, the hardship of Appalachian life has long been romanticised in American culture, not least in the country music that flourished in the mountains. The Paintsville exit of US Route 23 in Johnson County boasts a museum dedicated to the country music stars that grew up along the highway as it snakes through Kentucky coal country – from Loretta Lynn to Billy Ray Cyrus. Further west, at Cumberland Gap, we looked out across Tennessee to the distant Blue Ridge Mountains on the horizon. Somewhere in the blur was Dolly Parton’s empire at Pigeon Forge, and I was reminded of Alexander Wilson’s description of the Dollywood theme park in his book The Culture of Nature, in which he sums up its conceit as “People lived like this once; it was simple out here in the bush, but it was wholesome” (25).

Wilson compared the kitsch and pastiche of Dollywood to folk museums that have reassembled examples of vernacular architecture from the backwoods, noting that they claim greater authenticity but are just as staged and selective in the narratives they present. At the Museum of Appalachia in Tennessee, he observed: “The stories are meant to take visitors back to an earlier day: the years of victory over wilderness and savages. I look but can’t find documentation of the subsequent years of loss: loss of land to erosion, to inundation by reservoirs, to poverty and all the displacements of modern life” (26).

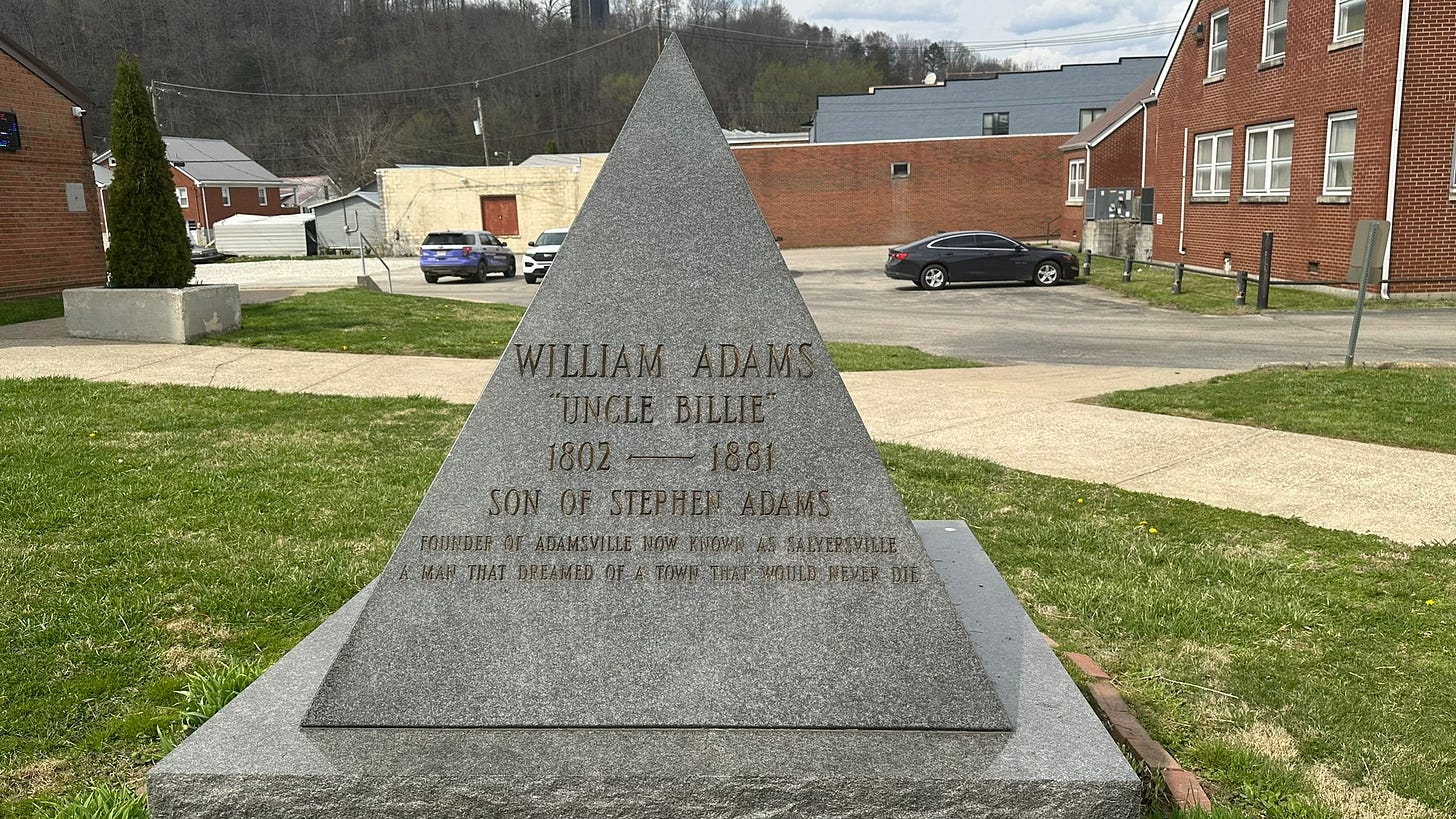

We visited a similar attraction, the Magoffin County Pioneer Village at Salyersville. It was closed at the time, but the site was open to wander between the relocated log cabins, barns and chapels. At its entrance stands a monument to the pioneer families of the district – Shepherd, Vanderpool, Gullett, Miller, Whitaker, Jenkins, Salyer and others – some of whom are still present in Magoffin County today.

The monument emphasised to us the relative recency of European settlement in eastern Kentucky. The region was surveyed in the mid 18th century, but most towns followed later in the early and mid 19th century. Salyersville was founded in 1849, Magoffin County incorporated in 1860 – recent enough for only a few generations to separate the pioneers and their living descendants.

Other sources also convey a sense of historical proximity to the frontier. One interviewee in Alessandro Portelli’s magnificent oral history of Harlan County remarked that “My ancestors, they come to this country, it was all wilderness, wild, you know. And it’s still, back into where I was raised, it is still; nobody lives back there, still wilderness”. Recalling his childhood in the 1940s, he added: “when I was a kid we was raised just about like the pioneers” (27). In Pike County, a resident with deep local family roots told Arlie Russell Hochschild that “Before coal, we were living a tough pioneer life here” (28).

Back in Salyersville, a second memorial in the Pioneer Village commemorating the town’s founder, William Adams, poignantly states that he “dreamed of a town that would never die”. The fact that this sentiment is highlighted suggests that the alternative prospect, that the town could die, is in the local consciousness. Does living somewhere that didn’t exist 200 years ago make the possibility that it could once again cease to exist more real than, say, in a European village with a thousand year history? Does place feel more fragile in a small town where the once core industry has gone than in a larger city or a prospering agricultural district? After rallying in the early 2000s, the population of almost every county in Appalachian Kentucky has fallen in the last decade. The population of Magoffin County decreased by 13% between 2010 and 2024, that of Maritn County and Owsley County by 17%, Knott County and Letcher County by 18%, Bell County by 20% and Leslie County by 22%. Harlan County has lost two-fifths of its population since 1980, Letcher County and Leslie County about a third of their population, and Breathitt County, Pike County and Floyd County around a quarter.

Moreover, does a familial connection to the founders of a community make the prospect of its erasure more personal? It is well documented in the rural studies literature that farmers commonly have a sense of inter-generational responsibility for properties that they have inherited and often experience guilt if they are forced to give up the farm. Is a similar sense of responsibility felt by the descendants of Appalachian pioneers and if so, has this emboldened antagonism toward politicians that make policies that undermined the region’s economic viability, or who simply seem not to care?

Defying Stereotypes

Pride in pioneer heritage and concern that its legacy is under threat has been harnessed by white nationalists and twisted into the mantra that ‘white men build this nation’ but have become marginalised and disrespected in a woke, multicultural society. There are no doubt some individuals in Appalachia who share this sentiment; but for most residents of eastern Kentucky the racism of white supremacism is abhorrent.

Arlie Russell Hochschild opens Stolen Pride with a white nationalist march organised in Pikeville by outside agitators in 2017. Only a handful of locals joined the march; most simply stayed away, while local authorities mobilised to contain the rally (and an anti-fascist counterprotest), protect non-white residents, and express their opposition to the marchers’ politics. Stressing that Pikeville citizens were part of neither protest, local commentator Jason Belcher wrote for the Huffington Post that “Conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats here don’t agree on much, but we agree extremism has no place in Pikeville” (29).

The counties of Appalachian Kentucky are overwhelmingly white, ranging between 93.9% and 99.25% of the population. Non-white residents tend to be relatively recent immigrants, well integrated, with many owning businesses or working in professional occupations such as medicine. There was however once a sizeable community of African American miners in Appalachia, descendants of freed slaves that had migrated from southern states. Although they enjoyed greater liberty than in the South and relatively cordial local race relations, African American miners still encountered racial discrimination and segregation and found that their jobs were more disposable when coal mining employment contracted. The black workforce in mining in Appalachia fell by 87.8% between 1950 and 1970 (compared with 73.5% for white miners) (30). Most moved away to industrial cities, but their story has more recently been recovered and celebrated as part of eastern Kentucky heritage.

Equally, in spite of J. D. Vance’s efforts to present Appalachian culture as ethnically Scots-Irish, the white population of eastern Kentucky came not only from Ulster, but also from Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Ireland, Wales, England and other European countries, contributing to a cosmopolitan milieu. Historian John Alexander Wilson records that the family ‘cultural baggage’ of Daniel Boone – the frontiersman who popularised the colonisation of Kentucky – included German crafts, a “Finnish-Irish log cabin, Irish livestock-handling and whiskey-making techniques, English books, Bibles and newspapers, Native American food crops such as maize and beans, and a male culture of hunting and woodcraft that was also learned from the Indians” (31). According to the American Community Survey, only 1.4% of people in Appalachian Kentucky actively describe their ancestry as ‘Scots-Irish’ – fewer than identify as English, Irish, German or Scottish (and the majority either don’t report an ancestry or identify simply as ‘American’).

The people of Appalachian Kentucky defy lazy stereotyping. They are certainly not all “the Appalachian Trump supporter as many people elsewhere imagine him – ignorant, racist, appalled by the idea of a female President or a black President, suspicious and frightened of immigrants and Muslims, with a threatened job or no job at all, addicted to OxyContin” (32). As writer and economic development practitioner Ivy Brashear put it:

“we are an incredibly diverse people in ethnicity, race, class, beliefs, and thoughts, just like any other place in America. We are the descendants of native peoples, slaves, subsistence farmers, coal miners, homemakers, school teachers, sharecroppers, business owners, Eastern Europeans and Africans. A rapidly increasing number of us have come from Mexico or South America. We are gay, straight, and everything in between. We are Democrats and Republicans, and more than anything, most of us don’t vote at all because of apathy and disenfranchisement. Some of us are coal miners, but more of us work in health care. Some of us live in abject poverty, a few of us live in extreme wealth, and most of us live in the middle, trying to desperately month to month to make it all work. In these ways, we are very similar to any other rural place in America right now, just trying to figure out our place in a twenty-first-century world that has, for the most part, left us to fend for ourselves” (33).

Nor do communities in eastern Kentucky lack agency.

One of the most enduring legacies of the War on Poverty has been the vitality of citizen activism in the region, often focused on issues and causes that are not usually associated with the Republican right. Writing at the start of the century, Dwight Billings and Kathleen Blee argued that “despite stereotypes of fatalism and passivity, Central Appalachia may well lead the nation today in the proliferation of vigorous citizens’ movements for social, economic, and environmental justice” (34). Local residents have fought against mountain-top removal and mine expansion, water pollution and toxic waste. They’ve formed action groups to clear litter, restore nature and provide clean water. They’ve opposed new prisons, initiated youth recreational activities, run job training programmes, and set up community newsletters. Talking to researchers at the University of Kentucky, we heard about projects and campaigns on local food, land ownership, labour rights, and the just transition. We learned about the community development work of LiKEN, such as community wealth-building from healthy forests and rivers, and about the women- and indigenous-led Appalachian Rekindling Project to restore cultural and ecological stewardship.

Left-leaning scholars and writers have cited activities such as these as evidence of an alternative, progressive Appalachia – but could the implied dichotomy be misleading? With over 80% of voters in Appalachian Kentucky backing Trump, is it not likely that there are individuals who see no contradiction in voting for Donald Trump and volunteering for a fairly progressive local citizens’ movement? Ronald Eller tells the story of a Republican county official in Letcher County who introduced door-to-door recycling and unionised local government as well as attempting to limit logging, ban smoking in public buildings, and raise the local minimum wage, before being ousted by a rival candidate backed by coal companies (35). Are there other Republicans like him in eastern Kentucky and have they stuck with the party as it has been refashioned by Donald Trump?

On paper, the voting record of Appalachian Kentucky, skewing heavily to Trump, looks like an exemplar of the polarisation of American politics. But could it possibly actually indicate something else? Could it imply an electorate in the small towns and rural communities of the region that refuses to be put in boxes or be tied to traditional party loyalties, but which is more eclectic in its politics and more fluid in its voting behaviour? Could the electoral geography of regions like Appalachia be less settled than has been popularly assumed?

Concluding Thoughts

We left Kentucky with more questions than answers, but questions were what we had gone there for. We will be heading back next year for a longer, more in-depth period of fieldwork and the ruminations that we’ve articulated above will inform the approach that we take: the issues that we focus on, the people we try to speak to, the data we want to collect, the questions we’ll ask in interviews, the codes we’ll use in analysis, and so on. We will also be thinking about them as we prepare for our other U.S. case studies in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, providing a starting point from which to consider the similarities and differences between these states and to look beyond stereotypes to understand the dynamics that are driving support for Trump across different rural settings. Furthermore, they will similarly form part of comparison with case studies of rural support for disruptive politics in parts of Britain and Europe. We will post more of these essays as we move through this process.

References and Readings

1 Dwight Billings, ‘Once upon a time in ‘Trumpalachia’ in Anthony Harkins & Meredith McCarroll, Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy (West Virginia University Press, 2019), Page 38.

2 Ronald D Eller, Uneven Ground: Appalachia since 1945 (University Press of Kentucky, 2008), page 57.

3 Ronald Eller, Uneven Ground, page 199.

4 Arlie Russell Hochschild, Stolen Pride: Loss, Shame and the Rise of the Right (New Press, 2024), page 23 and page 36.

5 Elizabeth Catte, What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia (Belt Publishing, 2018), page 16.

6 John Gaventa, ‘The power of place and the place of power’, in Dwight Billings and Anne Kingsolver, Appalachia in Regional Context (University Press of Kentucky, 2018), page 100.

7 Dwight Billings, ‘Once upon a time in ‘Trumpalachia’, page 53.

8 John Gaventa, Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence and Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley (University of Illinois Press, 1982), page 196.

9 J. D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy (William Collins, 2016), page 35.

10. John Gaventa, Power and Powerlessness, page 142.

11 Ronald Eller, Uneven Ground, page 36.

12 Dwight Billings and Kathleen Blee, The Road to Poverty: The Making of Wealth and Hardship in Appalachia (Cambridge University Press, 2000), page 328.

13 Ronald Eller, Uneven Ground, page 105.

14 Elizabeth Catte, What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, page 143.

15 Ronald Eller, Uneven Ground, page 184.

16 Quoted by Ronald Eller, Uneven Ground, page 33.

17 Arlie Russell Hochschild, Stolen Pride, page 89.

18 J. D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy, page 148.

19 J. D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy, pages 20-21.

20 J. D. Vance, Hillbilly Elegy, page 139.

21 Quoted by Dwight Billings, ‘Once upon a time in ‘Trumpalachia’, page 53.

22 Arlie Russell Hochschild, Stolen Pride, page 122.

23 Elizabeth Catte, What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, page 143.

24 Arlie Russell Hochschild, Stolen Pride, page 87.

25 Alexander Wilson, The Culture of Nature (Blackwell, 1992), page 210.

26 Alexander Wilson, The Culture of Nature, page 207.

27 Alessandro Portelli, They Say in Harlan County: An Oral History (Oxford University Press, 2011), page 27 and page 28.

28 Arlie Russell Hochschild, Stolen Pride, page 35.

29 Quoted by Elizabeth Catte, pages 173-174.

30 Thomas Wagner and Phillip Obermiller, African American Miners and Migrants (University of Illinois Press, 2004), page 49.

31 John Alexander Williams, Appalachia: A History (University of North Carolina Press, 2002), page 49.

32 Larissa MacFarquhar in the New Yorker, quoted by Elizabeth Catte, page 42.

33 Ivy Brashear, ‘Keep your Elegy: The Appalachia I know is very much alive’ in Harkins & McCarroll, Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy. Page 167.

34 Dwight Billings and Kathleen Blee, The Road to Poverty, page 325.

35 Ronald Eller, Uneven Ground, pages 246-247

.